Introduction

This will be a quick post covering Payment-In-Kind (PIK) interest. PIK interest is a feature of some debt instruments that allows the interest expense to be accrued, rather than paid in cash, for a certain number of years. This is where the name payment-in-kind comes from - the interest expense on the debt is paid in kind, i.e., with more debt.

Historical Context

While rare today, PIK interest was relatively common during the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, and therefore, it is often seen as a symptom of loose credit markets and boom times. Many prominent 2006 and 2007 private equity deals had debt instruments with PIK interest. Some of these deals did not go well.

Why Do We Care?

- PIK interest is uncommon today, but it still pops up occasionally.

- PIK interest is often associated with private equity, since it allows companies to support a bigger debt burden upfront and then gradually delever.

- Even if most private equity professionals never issue debt with PIK interest, it’s almost mandatory to be familiar with PIK interest and understand how it works.

- PIK interest is often included in modeling tests and private equity interviews as an extra little gotcha, which is silly, because it’s very rarely part of the job.

Why PIK Interest Is Appealing

To illustrate why PIK interest exists, let’s explore a hypothetical scenario:

- You’re running a private equity deal, and you’re in the process of arranging financing.

- You’re buying the target business for 1.0bn (10.0x LTM EBITDA).

- You have bank financing lined up for 3.0x leverage.

- The company can issue notes for an additional 3.0x leverage.

- So together, the bank financing and the notes get you to 6.0x total leverage, and let’s assume a PF interest coverage ratio of 2.40x.

- At this point, the private equity firm will be investing 400mm of equity (1.0bn transaction value - 600mm of debt). The projected returns are good, but not breathtaking.

- Unfortunately, your PF interest coverage ratio is already 2.40x, so it’s infeasible to raise additional debt.

- But the company has strong cash flows and solid growth prospects.

- What if you could raise more debt and delay the interest payments?

PIK interest has entered the chat.

- The private equity firm arranges an additional 100mm of junior notes, with a 3-year PIK (no cash interest expense for 3 years). These junior notes are expensive, because they’re the riskiest debt tranche in the capital structure, but they enable the private equity firm to invest less equity, which dramatically improves the projected returns.

- Furthermore, the company has 3 years to pay down its bank debt (and reduce its interest expense burden) before the junior note’s cash interest expense kicks in.

Takeaways

- PIK interest acts as a smoothing mechanism - moving some of the initial interest expense burden to later on. Much like a construction loan, interest expense is delayed and accrues.

- PIK interest enables companies to support a higher initial debt burden than they otherwise could.

- More debt, in the context of a LBO, means a lower equity investment and higher returns.

That’s why private equity professionals geek out over PIK interest - it’s quintessential 2007-era financial engineering.

How do we model PIK interest?

So now we know what PIK interest is and why it’s theoretically useful. How do we model it?

We’re going to be referring to the completed Excel template from our intermediate LBO tutorial.

This template already has PIK interest functionality built in, and we’re going to be explaining the different components in detail. We’re going to focus exclusively on the LBO_Final tab. The other tabs are intermediate steps explained in the tutorial.

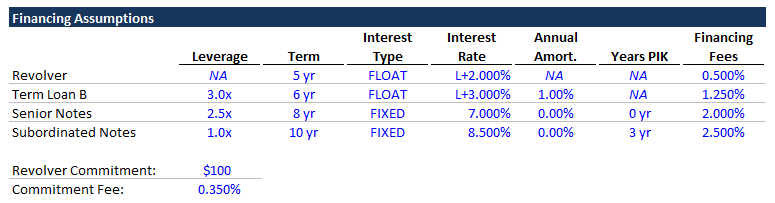

1. Financing Assumptions

At the top of the LBO, you can see the financing assumptions, where we include a Years PIK column for each debt tranche. This column specifies the number of years of PIK interest.

We’re assuming the subordinated notes have a 3-year PIK.

2. Debt Schedule

- When adding PIK interest to a model, build your debt schedule assuming no PIK interest at first.

- Generally speaking, only notes have PIK interest, and since notes are not amortized each year, the ending balance for your notes should be constant. (When we add the PIK interest, the ending balance for the notes will increase, since the interest expense during the PIK period is being accrued)

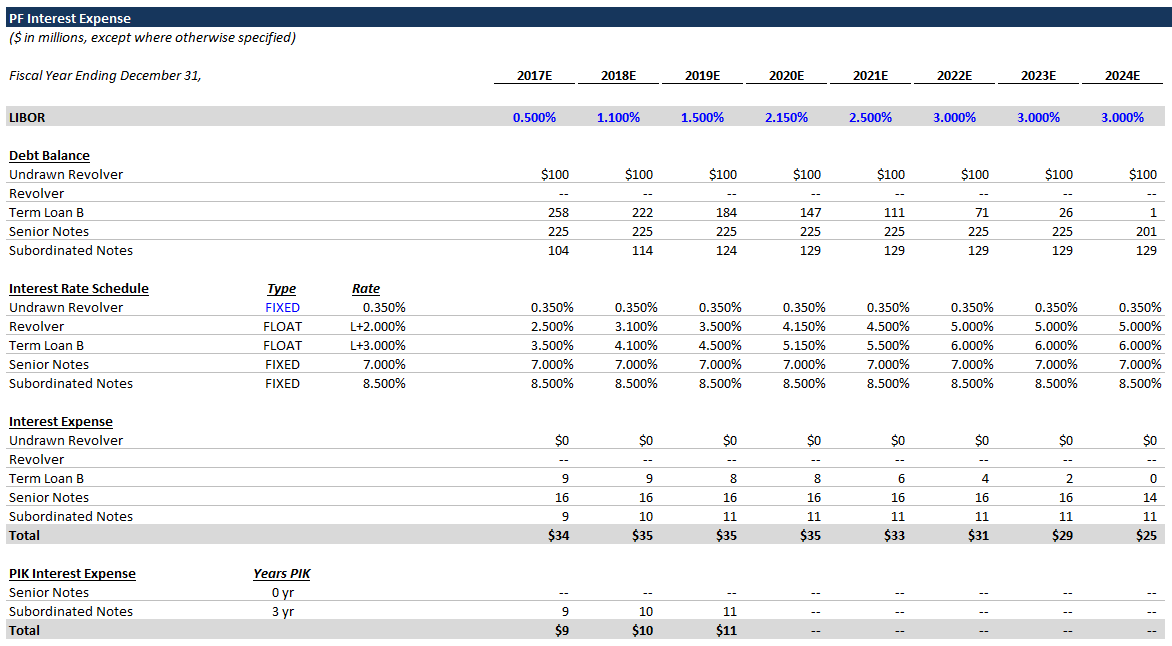

3. Interest Expense Schedule

- Likewise, build your interest expense schedule assuming no PIK interest. Although cash interest expense will change when we add the PIK functionality, total interest expense will not change. We still have to include PIK interest in the income statement, etc.

- Below the normal interest expense schedule, add a memo section for PIK interest. The calculations for this memo section are simple:

PIK Calculations

PIK Interest = IF(year count <= PIK years, include interest expense, 0) - Remember PIK interest is a noncash expense, since it’s being paid with more debt instead of cash.

4. Add PIK Interest to Debt Balance

- Now that we’ve calculated the PIK interest, we’re going to add it back to the debt balance.

- We’ll revise the ending debt balance calculation for our notes to be:

Ending Debt Balance (for notes) = Prior Period Balance - Mandatory Amortization - Optional Prepayment + PIK Interest

5. Include Noncash Interest Expense in Statement of Cashflows

We must add back noncash interest expense in the statement of cash flows, since our net income includes all interest expense (noncash + cash interest expense). In the LBO model, PIK interest is the primary component of noncash interest expense.

Conclusion

Now you should understand what PIK interest is, why private equity professionals like it, and how to model it.

Any discussion of PIK interest, however, would be remiss if it didn’t address the risks.

Risks

PIK interest is very risky. PIK interest allows a company to increase its debt burden in the near-term and pay more interest expense later on. In order for this to work, the company must be able to delever and then service the increased cash interest expense when the PIK period expires.

Furthermore, because PIK interest is riskier and is often associated with more aggressive capital structures, debt tranches with PIK interest are often expensive. Going back to our capital structure first principles, if the cost of debt is greater than the ROA, the incremental debt will actually decrease the return to shareholders. To put this in concrete terms, if we examine some of the 2007-era private equity deals that featured PIK interest, the cost of debt (with PIK interest) was sometimes greater than 12%. During the financial crisis, the ROA for many of these companies dropped well below 12%. Therefore, even when the companies managed to service their debt burden, these notes were not accretive to shareholder value.

To put it simply, PIK interest is an extremely aggressive feature, where everything has to go right for the private equity investor to win.

Next Steps

If you haven’t worked through our intermediate LBO tutorial yet, that’s a great place to start.

We also have a comprehensive (and free!) private equity modeling course.